Why Edtech Exits Will Defy Historical Trends

When we ask education entrepreneurs “Who will buy your company X years from now?” the answer, more often than not, is either limited or defies reality.

Entrepreneurs are busy building great companies that tackle extraordinary problems and impact the lives of (hopefully) millions. These aspirations make me most excited to partner with them. A company that has chosen the path of bootstrapping and raising debt capital may not need to consider an “exit.” But those that plan to raise equity capital must deliberate and understand the exit environment.

Perhaps not surprisingly, exit dynamics are not well understood by entrepreneurs and investors alike. This uncertainty is a result of the difficulty of looking five years out and predicting the set of buyers, their strategic motivations and the valuations they would pay. This exercise requires the most speculation in an already highly speculative business.

At a glance, the historical data on edtech exits is uninspiring, or at least when compared with the broader technology sector. But there are reasons to be optimistic.

Historical Reality? Lackluster.

We collected education M&A and IPO data from 2010 through H1 2015 and found 463 transactions. Financial details on acquisitions—particularly for small deals—are often not disclosed, so complete data is available only on a smaller subset of those 463. We break this figure into two categories:

- All transactions of any education company globally which we refer to as “global education” and

- A subset that includes only US-based companies and eliminates brick and mortar schools, thereby focusing on software and service companies. We refer to this set of companies as “US edtech.”

Based on this data, below are some of the tough historical realities education entrepreneurs (and investors) have faced.

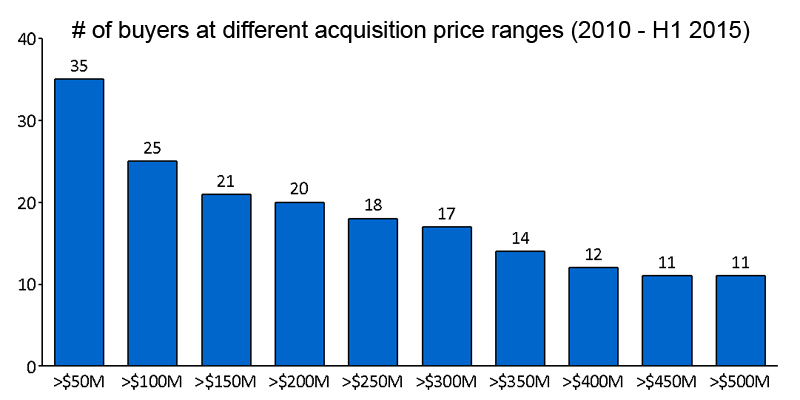

Buyer Shortage: There are only 25 buyers that spent more than $100 million on US edtech companies. (The figure for global education was 58). Let’s use some simple math to illustrate why understanding activity level at different thresholds is important. SJF typically looks for a risk-adjusted blended return of 5x on invested capital. This means that when we invest in US edtech businesses valued at $20 million, there are only 25 known buyers that historically would enable us to generate that return target.

Half of these 25 potential buyers may not have strategic interests in the company. Others may be sidetracked with other internal priorities or acquisitions. If we’re lucky, we may be left with five or so parties that could engage in real acquisition discussions.

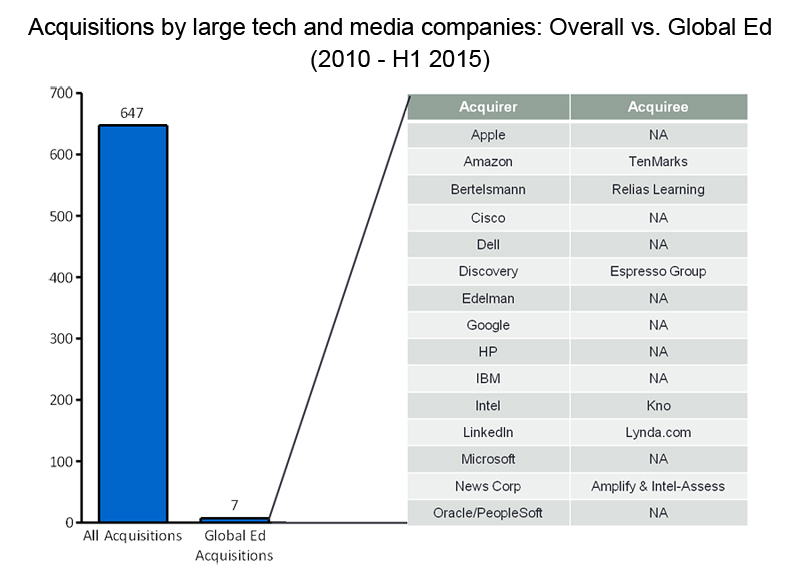

The Google Exit Mirage: In response to the question “Who will buy your company in X years?” I more often than not hear big tech and media companies listed. That’s a bad answer. Or at least reality would beg to differ. I call this the “Google exit mirage” or “Goo-rage.” While these large companies are ostensibly “active” in education, data reveals that of the 647 acquisitions they have made since 2010, only seven, or around 1%, have been in education.

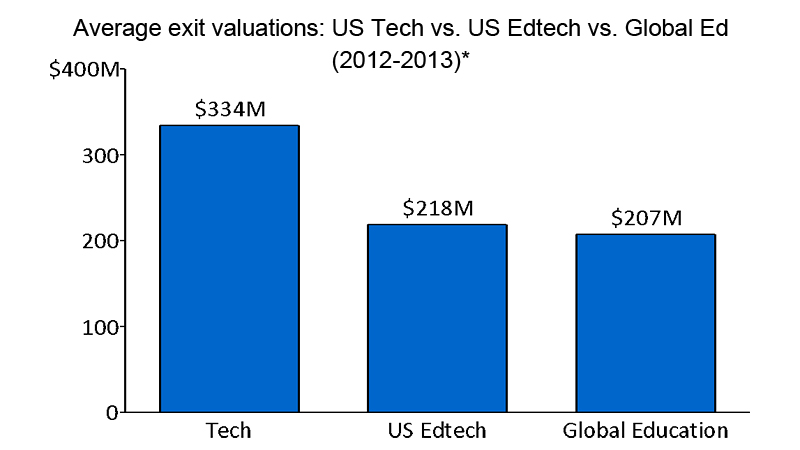

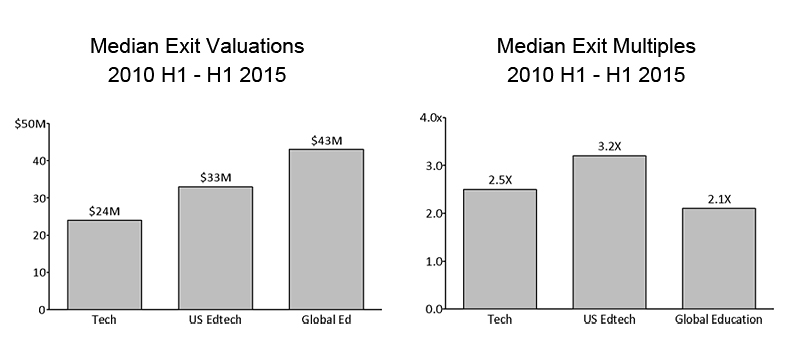

Subpar Valuations: The average transaction value involving education acquisitions are less attractive when compared to the broader technology landscape. The below chart show how exits for education companies have underperformed.

The above chart shows data for only 2012 and 2013 and excludes transactions below $15 million. If you include the entire data set from 2010 through H1 ’15 the average for US edtech was $182 million with global education at $162 million.

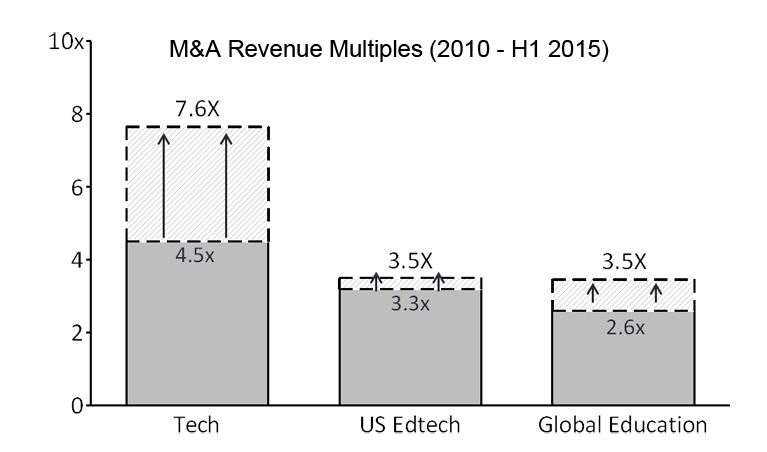

Lukewarm Multiples: The revenue multiples paid for acquired US edtech companies tend to be relatively sober when compared with broader US tech. This was evident in both of the data sources we examined, with one showing an average of 3.3x in US edtech versus 4.5x in broader US tech and another showing 3.5x versus 7.6x, respectively.

Few IPOs: The education data above focuses entirely on acquisition data and not on initial public offerings. As a fund, we rarely expect IPOs regardless of sector since they are a relatively rare phenomenon, although in edtech they’re even more exceptional. CB Insights shows that edtech IPOs between 2010 to H1 2014 represented 3% of all exits; during the same period the rate was 12% among all VC-backed SaaS companies.

Is edtech a bad sector to invest in? Perhaps, based strictly on historical data and when compared with the broader technology industry. But we see a bright(er) future.

The Case for Optimism

It’s possible that the edtech sector has arrived at the much vaunted inflection point. Every year we find more and more companies with revenue and sustainable business models. Today, it’s a regular occurrence to hear pitches from companies that have dozens of customer accounts and $1 million or more in recurring sales. This is different than in years past. This is happening for a variety of reasons; the three biggest ones are:

- More accountability: There is more scrutiny of K-12 and postsecondary institutions to improve performance.

- Infrastructure: Mary Meeker’s 2015 State of the Internet report identifies education as a market in which the impact of the Internet is “just beginning.” A recent Houghton Mifflin Harcourt survey of educators reveals that only 23% of students are using a laptop or desktop daily to do class work (and only 9% on tablets). This is changing as one-to-one adoption gathers steam.

- Streamlined distribution models are emerging that enable smaller entrants to elbow their way into domain historically dominated by larger companies that rely on “feet on the street” distribution models. “Freemium” models are working in some cases (Newsela and MasteryConnect to name two). Similarly, social media, especially Twitter, is another low cost medium that companies are leveraging intelligently to stimulate leads and grow their business.

Assuming these trends hold true, I think we’ll see two things:

1. Tech Giants Will Eventually Come: While it frustrates me to hear entrepreneurs citing big tech and media companies as likely acquirers, they may be on to something. While activity is still nascent, it does seem like these big fishes are taking this market more seriously. One can point to the IBM-Apple partnership, Google’s continued expansion of Google Classroom or their fund’s investment in Renaissance Learning, and LinkedIn’s acquisition of Lynda.com as anecdotal evidence. Other data suggest the giants will look at education more closely:

- M&A Activity: While the table above on acquisitions over the last five-and-a-half years by large tech and media companies illustrates their rarity, five of the seven acquisitions have come in the last two years.

- Conference Participation: The leading edtech conference for investors is ASU+GSV Summit. Between 2014 and 2015, attendance from major tech and media companies grew from 38 to 59 attendees (or 55%, versus the overall conference attendance growth at 24%). This is tenuous data, but suggestive of growing interest.

2. A Growing Middle Class: Like any maturing industry, edtech will see a growing middle class of prospective buyers. We’ve seen this in technology where there are scores of relatively unknown companies that, while not being able to spend more than $500 million on acquisitions, can entertain transactions of $100 million through their own capital, third-party funding or through a mix of cash and stock. We’re seeing the emergence of this middle class in education. These companies may currently not be able to execute 9-figure deals, but they might be positioned to in the near-to-medium term. These include Achieve 3000 in the K-12 market, Instructure and Chegg in postsecondary, and General Assembly and Pluralsight in continuing education, to name a few.

These forecasts are more aspirational and less evidential, but the dynamics are encouraging. If we go back a few years, M&A and IPO data for the “sharing economy” (such as Uber and AirBnB) would likely have suggested it too was an unattractive niche. So while historical data can surely be informative, succeeding in this industry means being able to read the tea leaves and detect changing trends that may make tomorrow different from yesterday.

What Does This Mean?

Headlines in the tech media often speak of the growing number of tech “unicorns” (companies valued at over $1 billion). Education technology companies are different. Let’s embrace the mules and stop chasing the unicorns. Even with average exit values of $182 million and revenue multiples of 3.0x, the industry can still support great edtech companies with impactful visions.

While education companies may not experience Uber’s hockey stick growth, an argument could be made that they are less volatile and have more predictable and proven business models and customers. Here’s one data point: while average valuations and revenue multiples paid are higher for the broader tech industry, the median is lower. This suggests to me that while there may be more chance for stratospheric financial returns in tech, there is also a greater likelihood for subpar financial returns.

What does this mean for entrepreneurs (and investors)? In short, capitalize businesses carefully and manage expectations that are grounded in historical realities while keeping a pulse on future trends. Here’s what we recommend:

Be reasonable on valuations. Getting the highest valuation is not always the best thing for a company, even when it may feel validating. With great valuations come (commensurately) great expectations. Again, historical reality lays out a case that even with strong performance market realities may temper what is reasonably achievable.

Consider capital efficiency. Valuations that require companies and investors to generate a sale exceeding $100 million should make you nervous. The fastest way to tie your hands to this type of outcome requirement is to raise lots of money.

The age-old struggle of capital raised and management dilution means that every new round of capital raised leads to valuations that can swing artificially upward. This means the newest investors can demand the company to defy exit odds in especially extraordinary ways. If a company is raising lots of capital at high valuations then it really must be one of those very few that has a shot at being an exceptional breakout story. SJF has certainly invested in these companies in the past but they’re rare.

Are you the exception? If valuations are high, can you lay out a plausible case for why your company has a real shot at being acquired from a non-traditional education buyer like Google? Content companies (i.e. math, ELA) don’t often make convincing cases (although Amazon’s acquisition of TenMarks was a particularly anomalous case).

You might make an reasonable case if you are a platform company or have a shot of attracting interest from other sectors. For example, Presence Learning services the K-12 market but also provides speech, occupational and other therapeutic services where they can draw interest from the healthcare industry.

Get to know prospective buyers early. Don’t wait until you’re interested in selling your business before having conversations with prospective acquirers. Get to know the right people in the relevant business units and corporate development teams long before this point. Those conversations can be informal; don’t discuss sensitive data, but share enough to keep you top of mind. See where formal partnerships may be prudent.

Developing these relationships can be a huge distraction and frequently unproductive, especially early in a company’s evolution. But, when successful, they can also help to illustrate how two businesses can fit seamlessly together and crystallize why your company can offer synergistic value to that partner. A great example of this path was ALEKS which developed a strong partnership with McGraw Hill long before that acquisition was made.